You might sing songs with village folk and play along with Tchia’s ukulele. Tchia’s visits to villages are typically accompanied by short, cinematic sequences of everyday life, some of them minigames that you can choose to participate in. But as a window into the life of another culture, it’s fascinating.

Outside of the terrain, a lot of those sights are inconsequential in the scope of Tchia as a video game. But if you slow down and take it all in, the sights you see along the way become the main drawcard. If you find yourself in the mindframe of wanting to rush towards the next objective, you’ll have a terrible time, as the only way to precisely pinpoint your location is by finding the odd signpost. Finding waypoint markers, collectables, towns, and people requires you to observe your immediate surroundings, attempt to place them on the map, and triangulate your position that way. Tchia makes the very bold move of providing you with only a static map of your surroundings, without explicitly telling you where you are on it (though Tchia can narrow down a general area for you). The game appears to be designed to make sure you concentrate on your surroundings, and not a marker on a minimap, by virtue of the fact that there is no minimap. However, focus on the journey itself, and smell the roses with each step you take, and the true joy of Tchia will reveal itself to you. Much faster shortcuts present themselves as you explore the world, but they don’t make your desire to travel any more compelling.

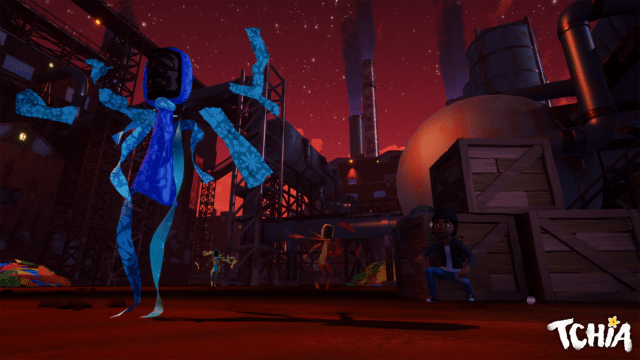

It’s old-fashioned open-world design made more egregious by the long distances you have to travel, how arduous it can be to get there on foot or sea, and lightweight character movement that sometimes lacks the precision needed to confidently balance on precarious structures. To find these items, you need to trek to lookout points at high-altitude locations, reveal local points of interest, and then journey to find the thing you need.įixate on this constant string of quests, and Tchia can be a slog. It later becomes clearer that the reliance on collectables are framed as something culturally intrinsic to the identity of Tchia, in the form of a traditional custom to offer local village leaders gifts in exchange for their guidance. Curiously, the game seems to both denounce it (given the clear use of industrial locations as enemy outposts and antagonistic locations) and embrace it at the same time, with the prevalence of claw machines and gold trophies playing their role in building out an enormous dress-up wardrobe for Tchia.įrameborder="0" allow="accelerometer autoplay clipboard-write encrypted-media gyroscope picture-in-picture web-share" allowfullscreen> It’s a jarring invasion of modern capitalism into the natural environs of the locale, both physically and ideologically. The first major lead to finding the big bad results in the young Tchia coming up against corporate bureaucracy, requiring her to sign endless reams of paperwork in the lobby of a towering monolith, and agree to provide a list of specific items to book an appointment. This rudimentary flow is something Tchia feels keenly self-aware of. What much of the game eventually boils down to is the act of exploring the world, finding collectable items, returning them to quest givers, and then finding what you need next. In the game’s opening hour, you begin feeling as lost as the young Tchia would, as she has seemingly never left her island, sailed, or interacted with the outside world before. Tchia begins by casually flitting through dozens of tutorial pop-ups, for countless small systems, while at the same time providing you with absolutely no guidance at all. It’s ambitious in scope – the game immediately lets you loose on a vast archipelago, sailing raft in tow, and tasks you to use your own intuition to do the best on the journey ahead.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)